Two names that should belong to the list are Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Makhdoom Mohiuddin.

Makhdoom gave priority to politics over his poetry- representing the Communist Party of India as an MLA in Andhra Pradesh while Faiz Ahmed Faiz in a metaphorical sense, and in a reversal of roles, substituted the lack of the political Left in Pakistan with his poetry. Sahir Ludhianvi wove magic with his uncanny, and unsurpassed ability to lyricize complex ideas, including ideological, into a brilliant tapestry of words making films his terra firma.

Kaifi Azmi and Ali Sardar Jafri together tread the path of literary activism, practically being the official poets of the Communist Party of India.

It would be futile to look for Kaifi Azmi, the man, in his film lyrics. They represent him only partially and those that do, bring out only the personally romantic side of him, specially in those sung by Mohammad Rafi in his mellow, bass elegance. Kaifi lacked the lyricism of Sahir that appealed to Bollywood movies and also the great literary sweep of Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

What Kaifi excelled at was the nazm, marking as he did, the break from the classicism of the ghazal form. As one of the angry young men thrown up in the aftermath of the Civil Disobedience Movement, at the time when it was very heaven to be young- the time of Jawaharlal Nehru's youthful swerve to socialist ideas, the formation of the Congress Socialist Party and the radical appeal of the Communist Party of India under P.C. Joshi who made culture as one of the 'fronts' on which the party had to fight in its struggle for socialism- much before Antonio Gramsci's concept of cultural hegemony came to be known and gain credence.

Kaifi was one of the major activists of the Indian People's Theater Association in his younger days and in 1986 made a valiant effort to revive the movement as its president. He was known for his closeness to the CPI, and even once had a spat with Sahir when he accused the latter of compromising his lifestyle while proclaiming his leftist political commitment.

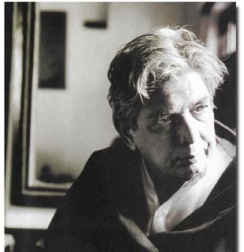

I remember Kaifi Azmi, Comrade Kaifi to us youngsters, reciting his famous nazm

Naujawan, after a spate of street dramas enacted by various groups in the IPTA troupe. His recitation was the last one as night crawled around us and a mild March breeze began to blow. His voice boomed in the pin drop silence, what a voice he had !

Raah agyaar ki dekhain yeh bhale taur nahinHum Bhagat Singh ke saathi hain, koi aur nahin.Zindagi humse sada shola e jawaani maangeIlm o hikmat ka khazana humdaani maangeaisi lalkaar ke talwaar bhi paani maangeaisi raftaar ke dariya bhi rawaani maange(That we would wait for others to take lead, does not suit us,

We are the comrades of Bhagat Singh, and none else

Life beseeches us our burning youth

The treasures of knowledge and courage

A cry so sharp that the swords may cry out

Such an electric flow that the oceans may look to us for inspiration)

At its most sensitive turns, Kaifi Azmi's poetry was meant to highlight the life of the poor and the suppressed, and at its most inspired movements, meant to inspire the young cadre of the communist movement to go out and work for upliftment of the "insulted and the humiliated". Kaifi Azmi had once proudly declared: I was born in colonial India, I have lived in an independent India, and will die in a socialist India.

Kaifi lived to see the dreams of his youth smothered as fort after fort of existing socialism collapsed in East Europe and its citadel, the Soviet Union. He was shell shocked.

And even in his silences he spoke for the grim silence of all those who had been inspired by the message of the October Revolution. After the fall of the Soviet Union, he did not speak for many months, and neither did he write.

It was the attack on Indian secularism on 06 December 1992 that awoke the activist poet in him and he wrote the nazm invoking Lord Rama.

Towards the end of his life, he returned to his roots, the small mofussial town of Azamgarh, building a high school for girls and a hospital. He had written:

Woh mera gaanv hai, woh mere gaanv ke choolehKe jinme shole to shole, dhooan nahin milata(That indeed is my village, and those indeed are the ovens of my village

In which, not to speak of the fires, even the smoke is not seen)

In the more famous matla of this ghazal, he had expressed the restlessness that inspired him:

Main dhoondta hoon jise woh jahan nahin miltaNai zameen, naya aasmaan nahin milta(The world that I search for, I do not find,

The New World, the New Heavens I do not find)

To look for Kaifi, is to keep on searching the for new, better, more egalitarian worlds. And heavens that are more just. To remove this search from his poetry would be to take away its soul.

On a personal note, I had the opportunity to meet with "Comrade Kaifi" at Ajoy Bhawan in New Delhi in 1986. On seeing a bunch of youngsters from the Punjab, he gave me a pointed look, the tuft of hair on his forehead falling over his eyes, and asked me, referring to the Khalistanis: Why are these young men angry?

I did not have an instant answer. And perhaps the question in that context has become irrelevant. But then, perhaps Kaifi was also referring to his own younger days, and asking: What is it that makes young men (and women) angry?

He had spent a lifetime in poetry trying to answer this question.

***

Thanks to

Alok for having revived memories of Kaifi and for the link to the "

Kaifi aur Main" site.

Image Source