Imagining Punjab in the Age of Globalization

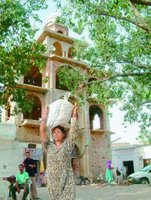

(a) Sikh Women grinding grain, 1945 (b) A gurudwara of Dalit Sikhs, 2004 (c) A modern agro industry

Guest post by Surinder S. Jodhka

Regions and regional identities are inherently fluid categories, constantly changing and being constructed by the people in given social, political and historical contexts.

The history of Punjab or Punjabiyat during the 20th century offers a good example of such a process. Though the Indian Punjab was reorganized as a separate state of independent India on the basis of language, it is often seen as a land of the Sikhs, despite the fact that Hindus and Muslims were in larger numbers in the region.

While dominant Hindu elites geared towards de- regionalizing themselves and claim opportunities opened up by the new nation, the Muslims elites of Western Punjab veered towards Urdu and legitimizing their dominance over the new nation- state of Pakistan.

Post- independence, Punjab also came to be identified as mainly a state with prosperous agriculture, the success of the agriculture also consolidated the position of the land owning classes/castes, the Jutt Sikhs.

The success of canal colonies in West Punjab had motivated the British colonial rulers to lay an extensive network of canals in the region. The Bhakra Nangal dam, one of the first major irrigation projects launched by the government of independent India, was also located in Punjab.

The Jutt Sikhs were also the ones who constituted the armies of the British Raj, and were the pioneers of the migration to Western countries a century ago.

Apart from the long tradition of migrations and global contact, the Indian Punjab also had a vibrant urban economy. Until recently the industrial growth rate of Punjab was higher than the average for India. Punjab continues to be among the more urbanized states of India and ranked fourth in terms of the proportion of urban population among the major states of the country during the 2001 Census. Against the national average of less than 28 per cent, the urban population of Punjab in 2001 was 34 per cent.

Of all the states of India, Punjab's growth rate in agriculture was the highest from the 1960s to the middle of 1980s. The annual rate of increase in production of food grains during the period 1961-62 to 1985-86 for the state was more than double the figure for the country as a whole.

While Punjab had 17,459 tractors per hundred thousand holdings, the all India figure was only 714. The same holds true for most other such indicators. These achievements have also been widely recognized.

At the sociological and political level, this growth of rural capitalism during the 1960s and 1970s imparted a new sense of confidence and visibility to the agrarian castes in different parts of India. Institutionalization of electoral democracy helped them dislodge the so-called upper caste elites from the regional and national political arena.

In the case of Punjab, the landowning Jutts had already been the ruling elite of the region. The success of green revolution and institutionalization of democracy helped them further consolidate their position. Even Sikh religious institutions came under their sway.

The triumph of agrarianism and the rise of the dominant caste farmers in the 1970s also set in motion a phase of populist politics at the regional and national levels in India. The newly emergent agrarian elite not only spoke for their own caste or class but on behalf of the entire village and the region. Their identification was not just political or interest-based and sectarian, as they saw themselves representing everyone, encompassing all conflicts and differences of caste, class or communities.

The rise of the Khalistan movement, a secessionist demand by a section of the Sikh community during the early 1980s, was a somewhat unexpected development since apart from its economic success, socially and politically too the border-state of Punjab had been a well-integrated part of India, having been at the forefront of the national freedom movement.

Not surprisingly, therefore, the rise of a secessionist movement in the state was for many a puzzle.

Contrary to much of the academic speculation that employed every known school of thought- from modernization theory to psychoanalysis, after some fifteen years of violence and bloodshed, Sikh militancy began to decline.

By the mid 1990s, the Khalistan movement was virtually over without having achieved anything in political terms. The end of the Khalistan movement, however, did not mean an end of 'crises' for Punjab. It was now the turn of economics and agriculture.

The green revolution had already begun to lose its charm by the early 1980s. Several scholars had in fact attributed the rise of militancy directly to the crisis of Punjab agriculture. By the early 1990s, there were clear signs of economic stagnation. Unlike some other parts of India, Punjab had lost out on the opportunities opened-up by the 'new economy' and investments of foreign capital that had begun to come to India with the introduction of economic liberaliztion.

The discourse of crisis found more ammunition during the post-reforms period when Punjab and some other parts of India saw a sudden spurt in the incidence of suicides by cultivating farmers.

By the turn of the century, agriculture in Punjab had lost nearly all its sheen, the emblematic Punjabi farmer seen nowhere in the new imageries of a globalizing India.

The changes that came about in the countryside with the success of the green revolution also produced a new class of rural rich who had experienced economic mobility through their active involvement with the larger capitalist market.

The new technology gave them tractors, took them to the mandi towns and integrated them with the market for buying not only fertilizers and pesticides but also white goods and an urban lifestyle.

Most agricultural households in Punjab today have become or are trying to become pluri-active, 'standing between farming and other activities whether as seasonal labourers or small-scale entrepreneurs in the local economy... Agriculture and farming is no more an all-encompassing way of life and identity.'

The available official data on employment patterns in Punjab has begun to reflect this quite clearly. For example, the proportion of cultivators in the total number of main workers in Punjab declined from 46.56 in 1971 to 31.44 in 1991, and further to 22.60 by 2001. While the share of cultivators has been consistently falling, that of the agricultural labourers had been rising until the 1991 Census. However, over the last decade, viz. from 1991 to 2001, even their proportion declined significantly, from 23.82 to 16.30. In other words, though two-third of Punjab's population still lives in rural areas, only around 39% of the main workers in the state are directly employed in agriculture. The comparable figure for the country as a whole is still above 58%.

The trend of moving out of agriculture is perhaps not confined to any specific class or category. While marginal and small cultivators seem to be moving out of agriculture, the bigger farmer is moving out of the village itself. The big farmers of Punjab invariably have a part of their family living in the town. Their children go to urban schools/colleges, and they invest their surplus in non-agricultural activities.

The rural social structure has also undergone a near complete transformation over the last three or four decades.

Over the last twenty years or so a large proportion of dalits in Punjab have consciously dissociated themselves from their traditional occupations as also distanced from everyday engagement with the agrarian economy and even investing in building their own cultural resources in the village, in gurudwaras and dharamshalas.

The growing autonomy of the dalits from the 'traditional' rural economy and structures of patronage and loyalty has created a rather piquant situation in the countryside with potentially far-reaching political implications.

In the emerging scenario, local dalits have begun to assert for equal rights and a share from the resources that belong commonly to the village and had so far been in the exclusive control of the locally dominant caste groups or individual households.

Seen purely through economic data, Indian Punjab continues to be an agriculturally developed region of the country, producing much more than what it requires for its own consumption. Even though occupying merely 1.53% of the total land area of India, Punjab farmers produce nearly 13% of the total food grains (22.6% of wheat and 10.8% of rice) of the country.

Interestingly, in terms of objective indicators, Punjab has been a 'progressive' state otherwise also. For example, in terms of the Human Development Index, Punjab is second only to Kerala.

The growth rates of Punjab – agriculture or industry – are no longer negative. Notwithstanding the frequent reports of corruption and scandals, the urban centres of Punjab seem to be picking-up in terms of growth of infrastructure and real-estate.

However, the Indian Punjab today needs to be re-imagined in more than economic terms alone. The canvas of its change is much larger and broader.

Given that Punjab has a large proportion of Scheduled Caste population, the newly acquired agency among the dalits can also have serious implications for regional politics.

The earlier hegemony of the rural Jutt culture is fast disintegrating and this will change the manner in which the larger interests of Punjab are articulated politically.

Globally, the Punjabi/ Sikh diaspora has been investing in building its cultural resources and participating in local political processes, getting elected to local and national political bodies, more than any other component of the Indian diaspora.

At home, the fast changing geopolitics of the world during the opening decade of the 21st century has important implications for the Punjabs and their futures.

Though the hostile visa regimes of India and Pakistan continue to be an obstacle, traffic of common citizens across the Indo-Pak border has been steadily increasing. The opening up the border between Indian and Pakistan has produced a sense of excitement and opened a window of hope for all shades and sections of Punjabis .

What implications would these new processes have for the manner in which we have imagined Punjab and Punjabiyat – within the national and global contexts? Will the processes of globalization and the new technologies enable the two Punjabs to rediscover their common cultural heritage? How would a loosening of the border and opening of trade routes influence the economies of the two Punjabs? Would the decline of agriculture and rapid urbanization of the state develop a new middle class imagery of the state?

Though it is not easy to answer these questions, some of these processes are sure to bring positive and enriching outcomes.

Surinder S Jodhka is Professor of Sociology, Jawaharlal Nehru University. He has done pioneering work on Dalits in Punjab and authored a number of works on the subject.

This guest post is further elaborated in 'The Problem' statement in this month's edition of The Seminar magazine "Reimagining Punjab" which he has edited. (online next month)

Image acknowledgements:

Comrade Sunil Janah's Site

Punjab govt Official Site

The Hindu

2 comments:

By the turn of the century, agriculture in Punjab had lost nearly all its sheen, the emblematic Punjabi farmer seen nowhere in the new imageries of a globalizing India.

Agriculture has lost its sheen only for farmers, but not for corporates. Infact as farm related suicides increase, & more and more farmers turn away from agriculture, corporates are entering Punjab in a big way. Obviously they foresee huge profits in agriculture, otherwise they would not be here in the first case.

To cite a few examples:

Reliance

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/articleshow/1594443.cms

http://www.punjabnewspaper.com/web/main.php?show_story=101&Reliance_enters_Punjab,_promises_to_make_it_agri_hub_of_nation

Bharti

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/2006/09/27/stories/2006092703030800.htm

http://www.punjabnewspaper.com/web/main.php?show_story=208&PM_inaugurates_farm_fresh_agriculture_centre_of_excellence_at_Ludhiana

A very exhaustive and comprehensive post, it raised a few questions for me though.

1. >Institutionalization of electoral democracy helped them dislodge the so-called upper caste elites from the regional and national political arena.

>In the case of Punjab, the landowning Jutts had already been the ruling elite of the region.The success of green revolution and institutionalization of democracy helped them further consolidate their position.

This is a very interesting insight and perhaps needs to be explored further- How come that while in other states (notably the UP), the upper castes were challenged but not in the Punjab.

2.>By the mid 1990s, the Khalistan movement was virtually over without having achieved anything in political terms.

In terms of not achieving any tangible gain as a separate state this may be true, but there is a clear change in the political alignment in the state- the Akalis emerged as the dominant political force, it also led to the diminishing role of the Communist Parties.

3. > For example, in terms of the Human Development Index, Punjab is second only to Kerala.

I am surprised specially with the news of the falling sex ratio in the state, I think this is not a very correct assessment of the state (probably other factors that are used to compute the HDI cancel out this aspect and also the lower literacy levels in the state).

I also noticed that in an otherwise very exhaustive and detailed analysis, the question of literacy and the gender aspect the post is totally silent.

Post a Comment